“One of the pathetic things in the pursuit of beauty in art is, that it is so hard to get a living by it. . . . The Rookwood Pottery has been a fortunate exception.”

–Maria Longworth Nichols Storer in 1889, quoted in Herbert Peck, The Book of Rookwood Pottery (1968), p. 39.One aesthetic prejudice, now discredited, holds that real or “high” art is distinguished from mere “craft” by the criterion of utility: Paintings, poems and symphonies are to be admired and understood, whereas pots, pans and baskets are things to be used. High and low, however, are not necessarily adversaries. Mundane objects possess their own manifest beauty.–Willard Spiegelman, Waterborne Crafting, Wall Street Journal, August 1, 2022, p. A13.

Among American producers of art pottery, the Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati, Ohio, was arguably the most important in terms of quality, innovation, longevity and volume. In its 87-year existence, Rookwood produced over 1 million pieces of art pottery, in more than 4,000 shapes and a wide range of styles and glazes.

Rookwood’s production was so varied over its lifespan that the company is sometimes referred to as several potteries in one. Compare its refined painterly creations to its earthy mat glaze production pieces, or its early lifelike florals to its abstract modern designs. Of another genre altogether are the company’s tiles and architectural faience.

Although not all Rookwood pieces were artistically successful, the extraordinary quality and creativity that sparked the company’s work gave rise to a remarkable legacy of art pottery. Here, then, from the perspective of the 21st century collector, is a survey of the company’s trajectory, focusing on the tendencies and qualities that make Rookwood a perennial favorite.

Early Days

Rookwood Pottery was founded in 1880 by Maria Longworth Nichols, whose father was a patron of the arts and prominent Cincinnati businessman. In the 1870s, Ms. Nichols, in association with other Cincinnati ladies, had developed skill at painting china blanks. The growing public interest in decorative pottery was greatly stimulated by the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, where ceramics from Europe and Asia made a deep impression on audiences. Of particular note was French “barbotine” ware, using colored slip (liquefied clay) to produce underglaze-painted pottery. Such pieces were also called “Limoges” ware, after the French city where the technique was practiced.

Maria Longworth Nichols was among the first artists in this country (along with Mary Louise McLaughlin and T.J. Wheatley) to successfully adopt the barbotine technique. In its early years, the Rookwood Pottery relied on the technique, often depicting piquant creatures inspired by Japanese pottery, such as bats, spiders and octopi. (See, for example, shapes S(10), S(13), 89; see also Hannah Sigur, American Pottery in the Japanese Taste, Style 1900 magazine, Spring 2009, pp. 46-53.)

In 1883, after the company won medals at the Exhibition of American Art Industry in Philadelphia and the Exposition Universelle in Paris, Nichols brought in as manager William W. Taylor. Under Taylor’s leadership, the business prospered, building its sales through a nationwide network of prestigious department and jewelry stores.

In 1889, Nichols transferred her interest in Rookwood Pottery to Taylor, who remained majority owner after the business was incorporated the following year. Also in 1889, Rookwood was awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris Exposition Universelle, greatly increasing the brand’s international stature and prestige.

Rookwood’s consistent success until Taylor’s death in 1913 is attributed in large part to his business acumen and artistic sensibilities.

How the Rookwood Style Developed

In 1883 Rookwood decorator Laura A. Fry developed a new technology that enabled the company to develop its signature style and become a leader in the fledgling art pottery industry. The new technique involved using an atomizer to create airbrushed backgrounds with smooth transitions and blending of colors. This provided an attractive base on which finely detailed images were drawn by hand, much in the manner of an oil painting, using colored slip. Finally, a clear or tinted glaze was applied. Thus, the form, background and focal decoration of each piece were integrated in a novel and artistic manner.

This technique, which became known as Standard glaze, was used with background colors primarily in tones of brown, yellow and amber, over which naturalistic depictions of plants, flowers or sometimes American Indians or other personages were painted. It spawned a raft of imitators (Weller, Roseville, Owens) and, it may fairly be said, launched the mainstream American art pottery movement. See The Craftsman magazine, December 1914, p. 302 (“the beginning of Rookwood pottery may be considered as marking a new era for the craft in America”).

During the mid-1890s lighter and brighter glaze lines gradually supplanted Standard glaze. Iris glaze, a glossy finish characterized by “bright decorations on backgrounds of light warm grays frequently blending into rich deep blue tones” (Peck I, p.51), is credited with garnering for Rookwood the Grand Prix at the Paris Exposition in 1900. It was produced until 1912.

Perhaps Rookwood’s most successful glaze line was Vellum, featuring idyllic, painterly tableaus rendered in pastel tones, covered with a parchment-like matte glaze. The decoration of many Vellum pieces followed the Tonalist movement in landscape painting, capturing quiet, misty moments in a forest or clearing, by placid lakes or streams, at the break of dawn, after rainfall or in twilight.

One writer ably describes the expressive qualities of Vellum glaze as follows: “These landscapes are vehicles through which the artists conveyed deeply personal feelings about nature. The soft edges of the forms seen through the Vellum glaze possess an ethereal, dream-like quality. The colors of sunrise or twilight skies and the cool colors of trees, water, and hills evoke a sense of gentle melancholia, of unfulfilled longing. Pastoral though these landscapes are, they rarely include people or animals or betray signs of human presence.” (Kenneth R. Trapp, Ode to Nature: Flowers and Landscapes of the Rookwood Pottery 1880-1940, p.35 (1980).)

Vellum pieces were produced between 1904 and 1948; many bear the cipher of Edward T. Hurley.

Rookwood artists also created Vellum-glazed ceramic plaques (large tiles), painted in the crepuscular Tonalist style. The example at left, executed by Sara Sax in 1914, measures 14 1/4″ x 9 1/4″. It sold at auction in 2019 for a hammer price of $23,500. Such plaques are highly collectible and actively traded but are not numbered, so they are not catalogued on this website.

Rookwood artists also created Vellum-glazed ceramic plaques (large tiles), painted in the crepuscular Tonalist style. The example at left, executed by Sara Sax in 1914, measures 14 1/4″ x 9 1/4″. It sold at auction in 2019 for a hammer price of $23,500. Such plaques are highly collectible and actively traded but are not numbered, so they are not catalogued on this website.

Other notable but rare glaze lines include Tiger Eye (crystalline) (see shape S(19)), Black Iris (shapes 1038, 1278(12)), Aerial Blue (shapes 273, 698(2), 765(2)) and Sea Green (shapes 583(4), 976).

In all these glaze lines, Rookwood decorators artfully depicted landscapes, seascapes and floral scenes, sometimes with the addition of birds, fish or animals. In the more successful examples, the decorators were able to achieve an extraordinary quality of detailed execution as well as skillfully blended transitions of color. Such pieces are highly collectible and command high prices at auction.

Probably the best known of the Rookwood decorators is Kataro Shirayamadani, who emigrated from Japan in 1887 to join the company. He returned to Japan around 1915 but rejoined the company in 1921 and continued to work there into his 80s. In addition to his individually-signed pieces, Shirayamadani designed many pieces for which molds were made, allowing numerous copies to be produced. He died in 1948. Even among the extraordinarily talented stable of Rookwood artists, Shirayamadani is particularly revered and his work commands a premium. (Photo Credit: Peck, The Book of Rookwood Pottery.)

The photo at right shows three of Rookwood’s most celebrated artists, circa early 1920s: Shirayamadani, Frederick Rothenbusch, and Ed Diers. (Photo credit: Virginia Raymond Cummins, Rookwood Pottery Potpourri (1991), p. 41.) Other noted Rookwood artists include Matthew A. Daly, Sara Sax, Carl Schmidt, Albert R. Valentien and Sarah E. (“Sallie”) Coyne.

The photo at right shows three of Rookwood’s most celebrated artists, circa early 1920s: Shirayamadani, Frederick Rothenbusch, and Ed Diers. (Photo credit: Virginia Raymond Cummins, Rookwood Pottery Potpourri (1991), p. 41.) Other noted Rookwood artists include Matthew A. Daly, Sara Sax, Carl Schmidt, Albert R. Valentien and Sarah E. (“Sallie”) Coyne.

Changing Times

The American art pottery industry reached its commercial and creative zenith between 1900 and the Great Depression.

In the early 1900s, Rookwood embraced the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement. The Arts and Crafts movement originated in nineteenth-century England as a reaction against the mechanized production and excessive ornamentation of Victorian-era furnishings. Taking its name from the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society founded in London in 1888, the movement emphasized simplicity, beauty and utility of design, with the overarching goal of restoring dignity and creativity to the applied arts. In the Arts and Crafts movement, “[w]ell-proportioned forms grew organically from a clean and direct expression of function, structure, and the nature of material; the result was that the new objects brought man back in touch with himself.” (Beth Cathers (with Tod M. Volpe), Treasures of the Arts and Crafts Movement 1890-1920, p. 8 (1988).)

The foremost American practitioner of Arts and Crafts design, Gustav Stickley, is known for sturdy, rectilinear furniture made from figured quartersawn oak, and for The Craftsman magazine, an influential journal devoted entirely to the Arts and Crafts movement. For a description of the goals of the Arts and Crafts movement and their adoption in the United States, see Wendy Kaplan, “The Art That is Life”: The Arts & Crafts Movement in America, 1875-1920, pp. 298-306 (1987); and Norman Weinstein, The Forest and the Trees: A Bird’s-Eye View of Arts & Crafts and Other Things, Arts & Crafts Quarterly, Vol. V., No. 1, pp. 32-35 (1991).

Production Ware

While continuing to produce individually-decorated, artist-signed pieces, Rookwood gave voice to the Arts and Crafts spirit in production ware, which was formed in molds, glazed in standardized matte colors, and sold in greater volume at lower prices. Matte glaze “is especially attractive, for it reflects the light in a soft, mellow way that is very restful to the eyes, and blends harmoniously with the woodwork, rugs, draperies and other furnishings of an interior.” Decorative Tile-Making: A Modern Craft and Its Ancient Origin, Craftsman Vol XXV, No. 6, March 1914, p. 615.

Impetus for adopting matte glazes and molded forms may have come from Artus Van Briggle, an innovator who worked for Rookwood from 1887 to 1899. Van Briggle was exposed to matte glazes while receiving special training in Paris in the mid-1890s. He went on to found his own highly respected art pottery working largely with molded forms and matte glazes. (See Peck I, pp. 67-69; Frelinghuysen, Eidelberg and Spinozzi, American Art Pottery, pp. 181-82; Robert Judson Clark ed., The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: 1876-1916, pp. 214-24 (1972).)

Rookwood’s adoption of matte glazes undoubtedly was also influenced by Grueby Faience of Boston. About 1898, Grueby began producing vases with a textured, mottled matte glaze sometimes likened to the rind of a melon or cucumber. The organic quality of the glaze was enhanced by modeled symmetrical patterns of vertical leaves and buds. Grueby’s synthesis of form, glaze and decoration was the ideal marriage of conventionalized and natural elements. Grueby quickly became (and remains) a touchstone of Arts and Crafts design. A telling indication of its powerful influence is the fact that Grueby pottery was included by Gustav Stickley in promotional displays, Arts and Crafts exhibitions, and photos in The Craftsman. (See American Art Pottery, pp. 160-73; The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: 1876-1916, pp. 178-90.)

Production using molds enabled Rookwood to expand its product line to include items such as bookends (84 different shapes were produced), paperweights, figurines, candlesticks and flower frogs. Matte glaze proved enduringly popular and hundreds of new shapes were introduced. By 1920 Rookwood had grown from a small pottery with a family atmosphere to a sizable ceramics producer with 15 kilns and around 200 employees.

Although Rookwood production pieces are not as highly valued by connoisseurs as unique individual works, their earthy matte glazes and symmetrical, often-geometric decoration reflect well the restrained, graceful aesthetic of the Arts and Crafts movement. Indeed, Rookwood production pieces embody the teaching of Maria Longworth Nichols’s husband George Ward Nichols, who stated presciently, “The best decoration for pottery is that of arbitrary forms or of natural objects conventionalized.” G.W. Nichols, Pottery and How It Is Made, p. 56 (1878). To conventionalize is to simplify forms found in nature, such as leaves, branches or flowers, by reducing them to a pattern that is more or less symmetrical, repetitive and geometric. This practice, central to Arts and Crafts design, was developed and illustrated by 19th century English design theorists. See Jonathan Clancy and Martin Eidelberg, Beauty in Common Things: American Arts & Crafts Pottery from the Two Red Roses Foundation, pp. 33-40 (2008); Michael Clark and Jill Thomas-Clark, The Not-So-Lost Fine Art of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Style 1900 magazine, Vol. 10 No. 4, Fall-Winter 1997, pp. 19-20; Bruce Smith and Yoshiko Yamamoto, Surface in the Arts and Crafts Home, Style 1900 magazine, Vol. 10 No. 1, Winter-Spring 1997, p. 59. See photo at left for an example of artist-decorated conventionalization, and check out the stylized tulips of shape numbers 2377 and 2378(3). See also Nancy Owen, Rookwood Pottery & the Influence of Arthur Wesley Dow, Style 1900 magazine, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 31-34 (2001).

Moreover, Rookwood’s mass-produced pieces served another core value of the Arts and Crafts movement — making objects of beauty and utility accessible to the average consumer. This points up a sad truth, namely, that because of high production costs and limited demand, hand-made pottery did not prove to be economically viable. By 1911 Grueby had ceased making vases, and by around 1920 Rookwood was focusing increasingly on production ware. Thus, the Arts and Crafts movement’s utopian ideal of restoring the dignity and craftsmanship of hand labor ultimately fell prey to the economic realities of industrial production. See Beauty in Common Things: American Arts & Crafts Pottery from the Two Red Roses Foundation, pp. 16-25, 45-47.

A Turning Point: The Z-Line

Rookwood matte glaze pieces produced between 1900-04 have a “Z” impressed following the shape number. (See, for example, shape numbers 120Z, 281Z and 302Z.) In 1904, however, the “Z” designation was discontinued and those shapes were renumbered from 912-1142. (See Peck I, p.69.) In Peck’s Second Book of Rookwood Pottery, Z-line pots are listed under their post-1904 shape numbers.

Some of the renumbered post-1904 shapes retained the glaze and decorative characteristics of the Z line. (See, e.g., shapes 913(33), 915(19).) Where such items are found on this website, the original shape number is noted in the Comments. Beware, however, of sellers who describe such items as “Z-line.” If it was made after 1904 and there’s no Z on the bottom, it’s not Z-line!

Z-line items were made in molds, but additional decoration was sometimes incised by hand. The extent of the hand work can be difficult to discern as it embellished the molded geometric patterns, which were in turn based on designs found on American Indian pottery. Thus many Z-line pieces are a sort of hybrid between production and hand-decorated ware. (See Anita J. Ellis, Rookwood Pottery: The Glaze Lines p.61 (1995).)

Some Z-line pieces are artist-signed, indicating hand-applied decoration. (See shapes 33Z(2), 51Z(3), 166Z(2), 235Z.) Moreover, some slip-painted artist-signed Z-line pieces were also produced, adding yet another variation to the line. (See shapes 3Z, 4Z(3), 53Z, 70Z(2), 192Z(5), 388Z.)

It may fairly be said that the Z-line was the most faithful and purest expression of the Arts and Crafts aesthetic in Rookwood’s oeuvre. Some Arts and Crafts aficionados prefer those rugged, simple pieces even to the more refined, painterly Vellum and Iris glazes. Z-line pieces accordingly command consistently healthy prices, often in the neighborhood of $75 per inch.

It may fairly be said that the Z-line was the most faithful and purest expression of the Arts and Crafts aesthetic in Rookwood’s oeuvre. Some Arts and Crafts aficionados prefer those rugged, simple pieces even to the more refined, painterly Vellum and Iris glazes. Z-line pieces accordingly command consistently healthy prices, often in the neighborhood of $75 per inch.

The Z-line vase shown at left, having an extraordinary modeled figure attributed to Anna Marie Valentien, sold for $32,760 in 2024. (Shape 192Z(6), 15″ h, 1901; collection of Museum of the American Arts & Crafts Movement.)

Characteristics of Production Ware

Rookwood production pieces made between 1900-1917 tend to have the most variegated, textured glazes, inviting to the eye and touch. (See shapes 77(8), 1044, 1139(25), 1795(38), 2095(9).) The “variations of shade and texture arise from delicate changes in the glaze occurring in the fire during the process of making . . . Such lack of uniformity is encouraged rather than avoided, for it has proved to be one of the most artistic factors in this form of decoration.” Decorative Tile-Making: A Modern Craft and Its Ancient Origin, Craftsman Vol. XXV, No. 6, March 1914, p. 615.

Moreover, as had been done with the Z-line, some production pieces made between 1904 and 1917 were embellished with hand tooling, adding to their appeal and value. (See shapes 77(21), 117, 950(47), 1044, 1342(5), 1358(33)).

After 1917, however, hand-tooling became increasingly rare and production glazes gradually became more standardized and uniform, losing depth and artisanal character.

The more desirable post-1917 production pieces have crisply defined incised decoration and lightened glaze effects highlighting the contours. (For example, see shapes 1795(8), 2174(6) and 2412.) On the other hand, some pieces have blurred or indiscernible contours, the result of overly thick glazes or worn molds. (See shapes 2122(4), 2123(6), 2425, 2854(3).) Such pieces are visually unappealing and their market value is accordingly reduced.

Early Z-line pieces notwithstanding, green is not the most common color matte glaze found on Rookwood production pieces. Rather, the most common color is a dusty rose with a gray overspray on the upper part of the piece. (See photo above.) Here, the atomizer technique that produced seamlessly blended colors in the Standard glaze was put to good use. (See Marion John Nelson, Art Pottery of the Midwest (1988), pp. 6-7.)

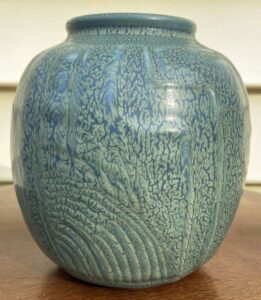

Various shades of blue are also common. (See shapes 1824, 2089(4), 2284(3), 2431(5), 2484(6).) Many other colors were produced; some less common but desirable matte glazes include speckled blue over tan (shapes 1795(41), 2322, 2415, 2814(4), 2921(10), 6070); rusty amber-brown (shapes 2564(16), 2163(2), 2814(3), 1795(24); 6090(4)); mustard matte (shapes 1807(3), 2135(31), 2168(4), 2404(3)); and chartreuse (shapes 77(8), 932(26), 1655(26), 1656, 1698(4), 1795(38), 1812(2), 2093(20)).

Curdled or vermiculated (wormy) glaze effects, sometimes called “frogskin,” are occasionally seen and add an attractive gnarly effect. (See shapes 2275(12), 2400 and 2428.)

A lively and affordable market subsists in the 21st century for Rookwood production pieces. That said, most American art pottery literature takes little or no notice of Rookwood production work, pejoratively branding it “industrial art ware.” One author even stated, “these mass-produced wares of Rookwood often embarrass art historians, ceramicists, and collectors.” Kenneth R. Trapp, Toward the Modern Style: Rookwood Pottery The Later Years, p. 14 (1983). While the cognoscenti may turn their noses up at Rookwood production pieces, it would be a mistake to overlook the elegant designs, simple beauty and rich glazes that make many such pieces pleasing and valuable.

Progressive Tendencies

As discussed above, the painterly, naturalistic landscape and floral vases are the most celebrated artist-decorated Rookwood pieces. Rookwood artists Charles S. Todd, William E. Hentschel, Elizabeth Barrett and Wilhelmine Rehm, however, developed a noteworthy alternative mode of individualized decoration. Working with robust, informal matte glazes, they created a more abstract, modernistic style of decoration, often partly or completely non-representational. Their stylized, jazzy pieces feature crisply incised motifs and flowing glazes. (See, for example, shapes 551, 604(5), 913(7), 922(2), 927(2), 2640 and 2818; see generally Trapp, Toward the Modern Style: Rookwood Pottery the Later Years.)

The earliest examples of this progressive style date to around 1912, rendering it downright visionary in the face of the staid tradition, dating back to the company’s origins in Limoges-style ware, of realistic renderings of natural scenes. The tendency continued until around 1930; later examples increasingly reflect Art Deco influences. (Although Peck II states that William E. Hentschel worked at Rookwood until 1939, no piece bearing his cipher dated after 1931 has surfaced in recent years.)

A problem that marred some examples of this style was glazes that ran excessively (or “crawled”), muddying the incised patterns. (See shapes 303, 922(2), 939(7), 947(3), 1004.)

Nevertheless, this sub-genre represents an example of the openness to change and progress that distinguishes Rookwood pottery. More importantly, artistically speaking, it is a felicitous addition to the Rookwood line.

Declining Fortunes

The company continued operating successfully through the 1920s, only to see its sales dwindle during the Great Depression. In the 1930s, sacrifices were made to balance commercial viability with the creation of quality artware. Saddled with operating losses and mounting debts, Rookwood’s production was curtailed.

During the Depression, many artists were let go by Rookwood. Two who stayed on, however, were Kataro Shirayamadani and Jens Jensen. Their pieces marked “S” (see Markings) from this period often find their way to market. (To find such pieces, put the artist’s name in the Search box; “S” items will appear first in the search results.)

By 1941, the company’s woes reached the point where operations ceased and a petition in bankruptcy was filed. The closing proved temporary, however; a group of investors led by automobile dealer Walter E. Schott and his wife, Margaret, bought the company and resumed production.

During the 1940s and 50s, the company emphasized high (glossy) glaze, presumably as an accommodation to changing tastes. While some artist-signed pieces continued to be produced, the high glaze production pieces from that era generally have a banal appearance and are not highly valued by today’s collectors. (For example, see shapes 6761 and 6865.) In fact, one of the pre-eminent art pottery dealers/auctioneers in the country, David Rago, stated sweepingly, “for all intents and purposes, Rookwood was finished by the time of World War II.” (Rago, American Art Pottery, p. 12 (1997).)

Continuing to experience difficulties, Rookwood changed hands several times before moving to Starkville, Mississippi, in 1960. The company closed again in 1967.

Rookwood’s Return to Glory: the Arts and Crafts Revival

In the 1950s and 60s, Americans put the hardships of the Depression and World War II behind them, embracing new industrial technologies and mid-century design innovations. (Tailfins, anyone?) Dark and ponderous, Arts and Crafts furniture became outmoded and passé. The modern wave drove Rookwood into desuetude as well; indeed, it sounded the company’s death knell.

In the 1970s, however, sparked by the 1972 Princeton University exhibition entitled “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: 1876-1916,” the moribund Arts and Crafts movement experienced a rebirth and revival. See Robert Judson Clark ed., The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: 1876-1916 (1972) (exhibition catalog with commentary by Martin Eidelberg and others).

As the dominant producer of Arts and Crafts pottery, Rookwood naturally was swept up in the revival. The brand’s renewed popularity reached full force in 1991 with the historic auction in Cincinnati of the monumental Rookwood collection of David and Kay Glover. The Glover collection reportedly contained more than 1,600 pieces of Rookwood, of which 1,210, almost all artist-signed, were auctioned off. See Riley Humler, The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of Rookwood Pottery, Style 1900 magazine, Vol. 11 No. 4, Fall/Winter 1998, pp.54-58.)

Second-hand copies of the Glover Collection auction catalog are still in circulation, as are catalogs of the Rookwood auctions which followed annually in Cincinnati, christened Rookwood II, Rookwood III, and so forth. (If you buy such a catalog, be sure it includes the prices realized insert.)

After peaking around 2008, Rookwood prices fell precipitously. In the following years, prices slowly but only partially recovered. Today, the better artist-signed and early production Rookwood pieces have the status of cult objects pursued by a small but devoted coterie of followers, while run-of-the-mill pieces pass for a pittance. (For detailed current pricing information, see Current Market Conditions, under About This Website.)

The small but ardent market for Arts and Crafts furniture, lamps and pottery has enabled dealers and auction houses that established themselves in the 70s and 80s—such as Rago, Toomey and Treadway–not only to survive, but to prosper, boosted by ever-increasing buyer’s premium percentages and the knack of offering rare and extraordinary items. Meanwhile, small and upstart auction houses specializing in art pottery face tough sledding.

As to the future of the market, the crystal ball is hazy. But if you’ve jumped on board the Rookwood bandwagon, chances are you’re in it for the joy and harmony it brings to your life, not investment returns. And that’s as it should be.

(Note: The Rookwood brand has resumed production under new ownership. It now sells updated shapes and styles, which are outside the scope of this website. This website is not affiliated with the current incarnation of Rookwood Pottery.)

Books About Rookwood Pottery

The foregoing is only a brief synopsis of Rookwood’s history and its place in the American art pottery movement. Fortunately many scholars and devotees have produced a wealth of books and articles that delve into greater detail on the subject, illuminating not only the historical facts but the artistic qualities that make Rookwood a perennial favorite. The following are particularly useful:

Herbert Peck, The Book of Rookwood Pottery (1968). Contains the definitive history of the pottery from the beginning until its demise in 1967, as well as a list of Rookwood artists and decorators and their ciphers.

Herbert Peck, The Second Book of Rookwood Pottery (1985). Companion to the foregoing. Offers some corrections to the earlier work, adds considerable new material (including an updated list of artists), and most importantly contains the complete record book of all Rookwood shapes from no. 1 (1880) to no. 7301 (1967), with descriptions, dimensions and a small drawing or photograph of each shape.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Martin Eidelberg and Adrienne Spinozzi, American Art Pottery (2018). An impressively detailed, beautifully illustrated and comprehensive survey of American art pottery. The book is largely devoted to the important art pottery collection donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by famed collector Robert A. Ellison. Regarding Rookwood, see pp. 72-89, 179-91. It should be noted that the pieces shown in this book are rare, museum-quality items, well beyond the reach of the average collector. However, a book such as this helps to develop an eye for quality and value. In this era of easily accessible online auctions, that understanding, combined with patience and assiduity, can enable even a modest collector to assemble a respectable collection.

Anita J. Ellis, Rookwood Pottery: The Glaze Lines (1995). Over Rookwood’s 80-plus year existence, the company’s thousands of shapes were adorned with a wide variety of different glazes. The product of endless research and experimentation by the company (reportedly 40,000 usable glazes were developed), the glaze lines were given poetic names loosely based on color, degree of matte or gloss, decorative style and texture. However, Rookwood failed to reliably mark its pieces to indicate glaze lines, to record dates of introduction, or to preserve photographic records. Moreover, the glaze lines overlap, so that many pieces cannot definitively be attributed to a particular glaze line. (Is that Conventional Mat, Modeled Mat, Incised Mat or Mat Moderne?) Since glaze lines can be amorphous and confusing, once you get past the most popular lines, like Vellum, Iris and Standard, they aren’t very helpful or informative. (On this website glaze lines, other than those just mentioned and the rare and valuable French Red, are not noted.) The author of this book tries gamely to sort them out, describing and showing examples of each glaze line, although she doesn’t provide shape numbers, which would be helpful. The best thing about the book is the photos, which are sharp, large and in color.

Marion John Nelson, Art Pottery of the Midwest (1988). Ohio was the home of the largest American art potteries, and important contributions to the field were made by potteries in adjoining states. Thus, geographical limitations do not preclude this author from presenting a comprehensive overview of design characteristics and historical development, including European and Asian influences and cross-fertilization between potteries. Recognizing that cast forms are not inherently inferior, eschews the dichotomy between hand-thrown, hand-decorated pottery and “industrial art ware” cast in molds. Instead, “organic” styles incorporating naturalistic imagery (most signed Rookwood, Roseville and Weller) are contrasted with “abstract” non-representational styles emphasizing shape and glaze (Rookwood production, Pewabic and Teco). (Aficionados of Fulper pottery will appreciate the latter approach, although that New Jersey brand is outside the geographic scope of the book. The latter approach is also more congruent with the Arts and Crafts aesthetic.) Most of the photos are small and in black and white, making it difficult to discern the qualities described. (Side trips to the internet for better photos are helpful.) Written to accompany an exhibition at the University of Minnesota, this is one of the most penetrating of such catalogs; it accordingly has become a fixture of the art pottery literature.

Robert Judson Clark ed., The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: 1876-1916 (1972). Rookwood’s decline began in the 1930s and culminated with the company’s demise in 1967. During that period, public interest in the Arts and Crafts movement became equally moribund. Many valuable pieces of pottery, furniture, lighting and metalwork were lost due to neglect. The 1972 exhibition entitled The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: 1876-1916, however, sparked renewed interest in Arts and Crafts design. This book is the catalog for that pioneering exhibition, which contained an extensive and remarkable array of Arts and Crafts objects, including “the first comprehensive display of American art pottery” (p. ix). The pottery display was curated by Martin Eidelberg, who adds his keenly perceptive analysis to this catalog. Eidelberg is a major figure in the Arts and Crafts revival (especially pottery) through his writings and his 2021 contribution of his pottery collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (A catalog devoted to that collection, entitled Gifts from the Fire, has been published by the Met.) This 1972 catalog is an historic and seminal document in the revival, which experienced a lull roughly between 2008-2020 but in the 2020s is being kept alive by a small but devoted fanbase. (For a colorful retracing of the Arts and Crafts revival as seen through the eyes of its key figures, including Eidelberg and Robert Judson Clark, see Judith Budwig and Jeffrey Preston, Redux: The Arts and Crafts Revival 1972-2012 (2013).)

For information about Clewell pottery, please visit ClewellDatabase.com.